“it would hardly be respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself in Europe without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other” (European monk, 1883)

Ancient Egypt has, it seems, always held a special allure for the West. From the curiosity of Greeks and Romans through to modern sightseers, Egypt is seen as an exotic treasure house filled with endless mysteries. Early British fascination with ancient Egypt was intertwined with political ambitions. After the defeat of Egyptian-Sudanese forces by the British in 1882, Egypt became a British ‘protectorate’ enabling the British Empire to considerably increase its influence in this strategic part of the world. This created a unique link between the African country and the European super-power.

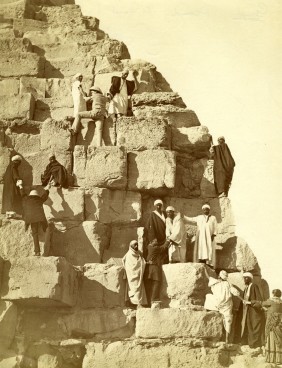

To wealthy British socialites of the 19th Century, Egypt represented the ideal travel destination where they could experience the wonders of an ancient civilisation, a warm climate to cure ills brought on by the inclement British weather, and collect tales and mementos with which to astound family and friends upon their return. It is through the surviving memoirs of early travellers that we learn much about the attitudes towards the people and customs of both ancient and modern Egypt. Personal accounts echo, yet also contrast with, Romantic, orientalising depictions of Egypt in 19th Century paintings. The collection of monumental sculpture and inscriptions were highly prized, yet these were very expensive to procure and unwieldy to transport. Acquisition of such impressive antiquities was largely the privilege of national governments, who competed to stock state museums. Mummies, however, were relatively easy to come by at this time and embodied many perceptions of Egypt as a strange, eternal, yet somehow familiar land.

The Gods and Their Makers, 1878 (oil on canvas), Long, Edwin Longsden (1829-91) / © Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museum, Burnley, Lancashire / The Bridgeman Art Library

The custom of purchasing mummies as souvenirs sparked a trend for ‘mummy unrollings’, popular in 18th and 19th Century Britain. Interestingly, although these events were destructive acts largely staged as entertainment, those conducting the theatrical ‘performance’ were often trained clinicians, well-versed in human anatomy and respected in their fields. The audience may not have necessarily understood what they were witnessing, but the person wielding the scalpel invariably claimed to; so although the resulting destruction of irreplaceable artefacts would be considered unforgivable to modern eyes, at the time it represented the best that scientific mummy studies could offer.

Despite their relative abundance, human mummies still posed logistical challenges for a traveller, as the Macclesfield heiress Marianne Brocklehurst describes during her 1873-4 trip along the Nile: the mummy she purchased was too much of an inconvenience to take home. In contrast, an animal mummy was the ultimate portable curio; a little piece of ancient Egypt that would fit neatly into a trunk for shipment to Britain, especially at a time when it was popular to hunt the living relatives of mummified species. Even the famous explorer and showman Giovanni Belzoni performed the “unrolling” of the mummified monkey. Many animal mummies in UK museums left Egypt with such travellers, were installed in their homes as talking points and objects of fascination, before being donated to museums during life as philanthropic acts, or bequeathed upon death when surviving relatives found little use for them.

One such traveller was William Wilde (1815 – 1876), Irish surgeon and father to eminent writer and poet Oscar Wilde. With a keen passion for archaeology, William travelled extensively in Egypt from 1830s, publishing his travel memoirs as ‘Narrative of a Voyage to Madeira, Tenerife, and along the shores of the Mediterranean’ in 1840. William’s account is typical of 19th Century adventurer-travellers and document Egypt at first hand, describing the people he met and the spectacles he witnessed. Wilde draws particular attention to the catacombs at the site of Saqqara:

“At length we arrived at where we could stand upright, and creeping over a vast pile of pots, and sinking in the dust of thousands of animals, we came to where we felt the urns still undisturbed, and piled up in rows with the larger end pointing outwards.”

“At length we arrived at where we could stand upright, and creeping over a vast pile of pots, and sinking in the dust of thousands of animals, we came to where we felt the urns still undisturbed, and piled up in rows with the larger end pointing outwards.”

He even mentions comparing ibis bones from the catacombs with some zoological specimens:

“In the museum of the school of medicine at Cairo, I had an opportunity of seeing and comparing both the black and the white ibis with the bones of those found in the mummy-pits at Sackara [sic]……..Great heat must have been employed in the preparation of these mummies, as the majority of them are so much roasted, as to crumble to dust on being opened.”

Sadly, we do not know the current whereabouts of the six ibis pots mentioned in Wilde’s memoir; however, like many early travellers, his account is immensely evocative, fuelled by the magic and mystery of ancient Egypt and the quest to report on the riches of its civilisation for the benefit of a Western readership.

This is a version of a chapter which appears in a new book to accompany the exhibition: L. McKnight & S. Atherton-Woolham (eds) Gifts for the Gods: Ancient Egyptian Animal Mummies and the British. Liverpool University Press.