In the first of two guest posts, Matt Szafran – independent scholar, palettologist and movie prop collector – examines the cult of the legendary Imhotep in ancient and modern times.

Imhotep is most commonly remembered as the architect of the Step Pyramid of the Third Dynasty (c. 2686-2610 BCE) king Djoser at Saqqara, which was the first known stone structure created. It is also worth remembering that Imhotep was responsible for the design and construction of an expansive mortuary complex of courts and chapels, the design of which was never replicated. The step pyramid is currently regarded as the first Egyptian pyramid, created from six layers of limestone mastaba style structures stacked atop each other. The pyramid was an enduring shape within Ancient Egyptian visual culture, which remained in use long after monumental pyramid building fell from favour. Perhaps this was, in part, the beginning of the cult of Imhotep, as the sculptor (referred to in later periods as a sankh or ‘one who gives life’) of such a revered design.

The Step Pyramid complex, seen from the south west

The tomb of Imhotep is yet to be re-discovered, or at least remains unattributed, and so the contemporaneous accounts of him all come from inscriptions on other artefacts and monuments. For example, a statue of king Djoser was found at Saqqara with an inscription, exceptionally, naming Imhotep and a list of his epithets, such as ‘the builder, sculptor and maker of stone vases’, the ‘overseer of masons and painters’, ‘royal chancellor’, ‘ruler of the great mansion’ and the ‘greatest of seers’. However the most unusual title discovered is that of ‘The King of Lower Egypt, the two brothers’, whilst there is debate over the actual meaning of this title it appears to imply that Imhotep was somehow an equal to the King – something completely unparalleled in Egyptian history and unique to Imhotep.

Statue base of Djoser with name and titles of Imhotep. Imhotep Museum, Saqqara

Imhotep’s reputation endured after his death, with the development of a funerary cult which venerated his literacy and his scribal and physician skills – something which must imply he was considerably talented in these areas. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri suggest that Imhotep became a medical demigod during the rule of the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2613-2494 BCE) king Menkaure – a mere 100 years after his death. We see this paralleled today, even in our modern disposable and ephemeral society, with scientists and engineers being remembered for their achievements decades or centuries after their death. Brunel for example continues to have monuments created and displayed all over the United Kingdom, in addition to giving his name to engineering universities, trains and being featured on modern coinage and in lists of the ‘Greatest Britons’.

Middle Kingdom (c. 1975-1640 BCE) tombs, such as that of king Intef, featured verses of the ‘Harper’s Song’. Some of these verses contained references to Imhotep and his teachings, illustrating that even royalty revered Imhotep’s work sufficiently to want it included in their funerary rituals.

This cult endured for centuries, with the ‘Turin Papyri’ illustrating that Imhotep’s epithets were increased during the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1077 BCE) where he gained the titles of ‘chief scribe’, ‘high priest’, ‘sage’ and the ‘son of Ptah’ – the latter essentially making Imhotep a demi-god. It was during this period that Imhotep also became the patron of scribes. Offering formulae on statuary include dedications that ‘the water in the cup of any scribe’ be offered as a libation for Imhotep’s Ka spirit. Perhaps scribes would have personal statues and dedications to Imhotep to offer prayers to in return for assistance in their work, just as they may have for Ptah and Thoth. In visual culture these depictions of Imhotep are always as a seated man, with a bald head or cap (similar to that of Ptah) and typically with a scroll opened on his lap.

Votive statuette of Imhotep. MMA 26.7.852a, b

Imhotep continued to be worshipped into the Saite Period (c. 664-525 BCE), over two millennia after his death, culminating in becoming one of the few non-royals in Ancient Egypt to be fully deified. He remained as the son of Ptah and his mother then became either Nut or Sekhmet, it was also around this time that Imhotep became associated with Thoth and was considered to be the god of medicine, wisdom and writing.

This association persisted into the Ptolemaic Period (c. 332–30 BCE) with the Greeks identifying Imhotep with Asclepius, their god of medicine. This association helped the cult rise out of the Memphis region and spread throughout Egypt. Imhotep’s main cult centre was, appropriately, established near to the Step Pyramid in Memphis, with other temples at Deir El Bahari, Deir El Medina, Karnak and Philae. His cultists would make pilgrimages to these sites to give offerings in return for curing health problems and for help and advice with difficulties in their daily lives. An inscription on a statue found in Upper Egypt lists six festivals created in honour of Imhotep each year, all of which would have involved music, dancing and banquets.

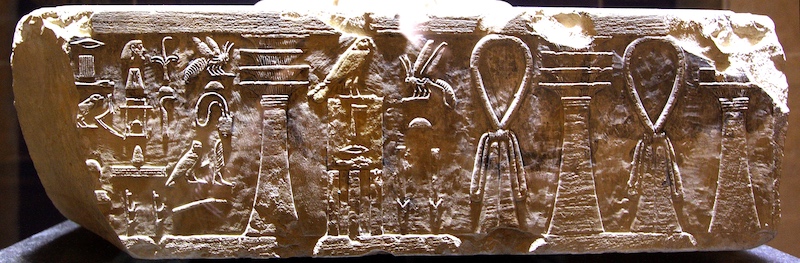

Figure of Imhotep, accompanied by Amenhotep son of Hapu to the right, at the temple of Ptah at Karnak

Imhotep’s cult waned with the Arab conquest of North Africa, with his medial writings surviving as long as the Christian era. However with the European re-discovery of Ancient Egyptian culture in the 19th Century reignited interest in Imhotep and his accomplishments. This renewed interest wasn’t solely by Egyptologists, and Imhotep took his place as a forefather of modern medicine. There are now medical papers and books written about Imhotep and the role he played in the history of medicine, the Faulty of Medicine building of the Paris Descartes University even has a carved relief of Imhotep.

The modern day cult of Imhotep may not make pilgrimages or hold festivals in his honour but it does still build monuments to him, it venerates his knowledge, wisdom and skill and it continues to writes about him. So really is the modern day cult all that different to that of millennia previous?

Part 2 – on the modern cultists of Imhotep – to follow…