A guest post by Dr. Nicky Nielsen, Lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Manchester, on a Late Period piece now published in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

This fine limestone stela in the Manchester Museum collection has no clear archaeological provenance. It most likely came to the United Kingdom in the collection of the early Egyptologist James Burton Jr in the early 19th century and from there passed into the collection of the banker Samuel Rogers (1763-1855) whose nephew, Samuel Sharpe, published a transcription of it in 1837. Upon his death, the stela was sold at auction in London and eventually ended up the collection of the Manchester cotton magnate Jesse Haworth. The stela was first published in translation by the founder of the Egypt Exploration Society Amelia B. Edwards in 1888.

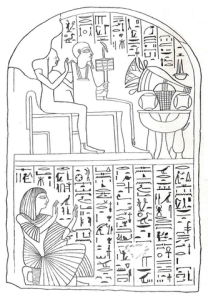

Acc. no. 6041

The stela is divided into three fields: at the top is a lunette with a winged sun-disk, two Wadjet-eyes and two jackals. The second field contains five figures: at the far right is the stela’s owner, Horenpe and standing before him are four deities identified as Re-Horakhty, Hersiese, Isis and Nephthys. Some traces of red paint are preserved on the body of Re-Horakhty, on Nephthys and on Horenpe himself.

The text is divided into two sections. The first comprise a brief prayer and a series of labels above the various figures: Words spoken by Ra-Horakhty, Great God, Lord of Heaven in order that he may give a good burial in the Necropolis! Horus Son of Isis, Divine Isis, Nephthys Mistress of Heaven. [The Osiris], the God’s Father Horenpe, the Justified before the Great God.

The main text is in the third register under the figures and starts with a standard Offering Formula: An offering which the King gives to Osiris, Foremost of the Westerners, Great God, Lord of Abydos so that he may give a voice offering of bread, beer, oxen and fowl, incense upon the fire, wine, milk, vegetables(?) and everything good, pure, sweet and pleasant for the ka [of] the Osiris, the God’s Father Horenpe, son of the similarly titled Osirimose, born of the Mistress of the House Mutenpermeset.

Transcription by Nicky Nielsen

The stela’s origins are unclear, but based on style it seems likely that it dates to the 26th Dynasty and may have originated from a workshop at the Middle Egyptian site of Abydos. A very similar stela also belonging to an individual by the name of Horenpe was found at this site in 1906 by the British archaeologist John Garstang and is now in the Garstang Museum of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool.

It is often the case in museums that apparently inconspicuous objects can turn out to contain very interesting bits of information. This is the case with this small (height: 12.4cm) flat-based beaker. It can be dated by its shape to between the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (c. 1700 BC) and is manufactured from a relatively fine Nile silt clay. Small amounts of chopped straw (so-called ‘chaff’) was added to the clay to make the vessel more stable during firing. Holes were punched along its lip prior to firing and allowed the vessel to be hung with strings. Alternatively, they could have been used to tie down and secure a lid. An inked inscription runs in two lines along the vessel’s body:

It is often the case in museums that apparently inconspicuous objects can turn out to contain very interesting bits of information. This is the case with this small (height: 12.4cm) flat-based beaker. It can be dated by its shape to between the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (c. 1700 BC) and is manufactured from a relatively fine Nile silt clay. Small amounts of chopped straw (so-called ‘chaff’) was added to the clay to make the vessel more stable during firing. Holes were punched along its lip prior to firing and allowed the vessel to be hung with strings. Alternatively, they could have been used to tie down and secure a lid. An inked inscription runs in two lines along the vessel’s body: