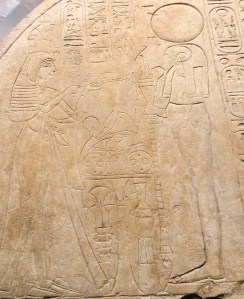

A guest blog from University of Exeter researcher Tara Draper-Stumm, who is researching the numerous Sekhmet sculptures of Amenhotep III at Kom el-Hettan. Here we reveal a previously-unidentified fragment from the Museum’s storerooms, likely from the same context.

This inscribed rectangular granite base with a pair of feet in the striding position, both broken at the ankles, are all that remains of a standing statue of the goddess Hathor (acc. no. 3309), commissioned by Amenhotep III. An inscription in two columns on the base reads:

Son of Ra, Amenhotep, Ruler of Thebes, given life

Beloved of Hathor, Lady of jubilees

The inscription suggests that the statue was commissioned in preparation for the first of Amenhotep III’s three Sed (‘jubilee’) festivals, which took place in his 30th regnal year.

Acc. no. 3309

The base measures 43 cm in length by 22.5 cm wide, and is 14 cm in height, with a cracked surface. Statue bases associated with the well-known life-size (or larger) standing statues of the goddess Sekhmet are approximately 30%-40% larger than the Manchester statue base, with three columns of inscription. The size of the Manchester piece therefore suggests it comes from a statue that was smaller than lifesize, perhaps 1 metre or so in height.

Sekhmet statues from Kom el-Hettan in the British Museum

While we know that Amenhotep III commissioned hundreds of statues of himself and the gods in the run-up to his Sed festival, embellishing temples the length of Egypt, the inscription would indicate this statue fragment came from Kom el-Hettan in Luxor, the site of Amenhotep III’s funerary temple, where his Sed festival was likely celebrated.

This statue fragment entered the museum’s collection in 1895-6, the gift of Jesse Haworth, a major supporter of the work of Flinders Petrie and the newly established Egypt Exploration Society. In return for his support, Haworth received a selection of Petrie’s finds. In the 1895-96 season Petrie excavated a group of funerary temples on the west bank at Luxor, his results being swiftly published as Six Temples at Thebes in 1897. Petrie did not excavate at Kom el-Hettan, since “de Morgan [Director of the Antiquities Service] informed me that he reserved the site of the great funerary temple of Amenhotep III for his own work.” However, Petrie was allowed to investigate the ruins of Merneptah’s funerary temple, near Kom el-Hettan. Here Petrie “discovered a large amount of sculpture which had belonged to the temple of Amenhotep III, as that had been plundered for material by Merneptah.”

Detail of Acc. no. 3309.

Petrie makes no mention of this statue fragment in his report, and no photographs of it survive in the archives of the Petrie Museum, where photographs associated with this excavation are to be found. However, Petrie does mention finding parts of statues of jackals “split up into slices…and laid in the foundations of Merneptah,” along with parts of sphinxes, inscribed blocks and parts of statues of Amenhotep III, among the foundation fill. It seems possible therefore that the Manchester Museum’s statue base could also have been used in Merneptah’s foundations and was found there by Petrie. The condition of the statue base would certainly suggest this. Petrie also made mention of the area being “under the high Nile level”, with evidence buried statuary much “swelled and cracked,” presumably from water damage over time. This description also relates well to the damage to the Manchester statue base.

Such a statue of Hathor may once stood in a shrine inside Amenhotep’s funerary temple, one of many hundreds of statues commissioned for the temple and employed in ceremonies associated with the King’s Sed Festival. It is unclear what happened to the rest of the statue. It may have been broken up and used in the foundations of Merneptah’s temple, like so many other statues from Amenhotep’s funerary temple. Presumably if the body or head had survived in decent condition in association with the statue base Petrie would likely have kept them together. Since this area of Luxor has been dug up repeatedly since at least the early 19th century, including by Drovetti, Salt, and Belzoni, among others, it is also possible that a further fragment of the statue survives in another museum or private collection.

Hathor cow head. MMA acc. no. 19.2.5

Evidence survives for smaller than life-size divine statues being made in the reign of Amenhotep III. A head of the goddess Hathor as a cow is in the MMA in New York (acc no. 19.2.5). Made from porphyritic diorite, the head is only 28 cm wide at the ears, and the back pillar measures 15 cm wide. While this is probably not the head for our statue base, it could suggest what the statue looked like when completed

While we may never know for certain where this statue base was found, or how it originally looked, it adds to an ever-developing picture of Amenhotep III and the incredible rates of statuary production during his reign.